Stagflation

Synopsis

Up until the 1960s and 1970s, mainstream economic thinking was that inflation and unemployment were inversely related. That was until many countries began experiencing periods of both high unemployment and high inflation.

Here we provide some background to the theories of stagflation as well as its possible causes.

Prices and Inflation

People tend to describe inflation as a general rise in prices, but inflation has historically meant an increase of the money supply, with the seemingly inevitable consequence of a rise in prices. To avoid confusion the terms “monetary inflation” and “price inflation” are often used to avoid confusion between the two.

Alternately, deflation is used to describe when prices fall, or when the money supply decreases.

Inflation and Unemployment

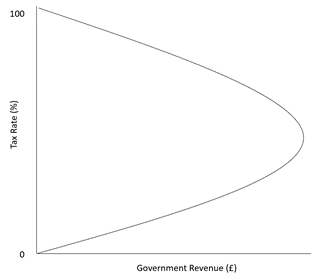

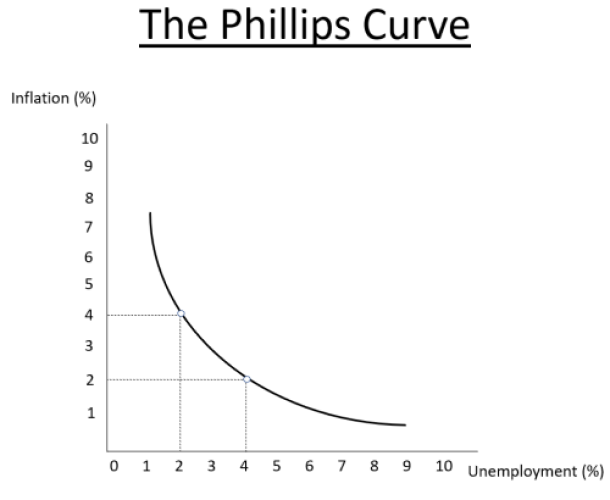

In 1958, economist William Phillips noticed that in times when unemployment was high, wages tended to stabilize or even fall. Likewise, when unemployment was low, wages rose. Although these patterns had been spotted before, this inverse relationship was illustrated by what would become known as the Phillips Curve.

Although it was only a trivial conclusion, the link between unemployment and inflation became central in mainstream economics and is still in use, albeit in a more complex form.

The Phillips Curve

In describing the Phillips Curve, the website Investopedia writes :

“…any fiscal stimulus would increase aggregate demand and initiate the following effects. Labor demand increases, the pool of unemployed workers subsequently decreases, and companies increase wages to compete and attract a smaller talent pool. The corporate cost of wages increases, and companies pass along those costs to consumers in the form of price increases.”

The theory led many economists and politicians to focus on interest rate targets and using fiscal and monetary policies to expand and contract the money supply when required.

What is Stagflation?

During the 1960s, the UK faced a period in which prices and wages were going up yet output was going down. On 17th November 1965, Shadow Chancellor Ian Macleod said:

“I can find no period—and I have checked this all the way back, with the possible exception of 1952—when in 13 years there was a year when the gap was so wide between what we should be doing, and we were in fact doing.

We now have the worst of both worlds —not just inflation on the one side or stagnation on the other, but both of them together. We have a sort of "stagflation" situation and history in modern terms is indeed being made.

…As I say, production has fallen by 1 per cent. or ½per cent. while incomes have gone up, perhaps, by 8 per cent. This can result only in two things happening in the months ahead; either a considerable increase in our import bill to meet the increased consumer expenditure or a very real rise in our prices. But what the First Secretary is trying to do is to conceal the rises that are likely to take place.”

The term made another appearance during the 1970s after the “Nixon shock” of wage and price controls, and the abandonment of the Bretton Woods Agreement, led to the 1973-1975 recession. This recession also saw high levels of inflation and unemployment.

Explanations for Stagflation

One of the most popular views on stagflation comes from Edmund Phelps and Milton Friedman (both Nobel Memorial laureates), who challenged the idea that there was any long term trade off between unemployment and inflation.

Phelps and Friedman argued that newly created money enters the economy and everyone has more money. This increases demand for goods and services as people spend more, which drives up prices. Demand for workers begins to increase and unemployment decreases. People gradually become aware that the original increase in money which drove their spending was temporary and they expect price inflation to increase, so they start to spend less. This weakening demand slows down production while unemployment goes up. We end up with high inflation and high unemployment.

In his article Did Phelps Really Explain Inflation?, Austrian economist Frank Shostak takes a number of issues with the Phelps-Friedman view. Firstly, the idea that money, created out of thin air, gives each individual now has more money, is false. Rather than being dispersed equally, some receive money first while others receive it later. Therefore, the first recipients are the beneficiaries of the new money, allowing them to purchase more goods at the expense of the late recipients. This is sometimes known as the “Cantillon Effect”.

Money created “out of thin air”, as Shostak writes, undermines real economic growth. Stagflation is another consequence of a loose monetary policy, to which both Shostak and Phelps-Friedman agree. Shostak asserts however that the result of monetary inflation “weakens the pace of economic growth and at the same time raises the rate of increase of the prices of goods and services.

Conclusion

The earlier links between inflation and unemployment, were in no doubt, an interesting discovery. However, correlation is not causation, as can be seen in the examples of the UK in 1960s and the US in 1970s. Phillips made a valuable contribution to the economic field with his work, however the conclusions drawn by others, after the fact have had disastrous results for currencies and markets.

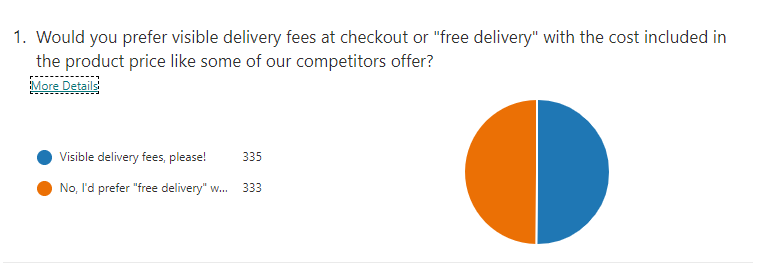

As we come to the end of 2021, inflation in the UK is set to hit 4% as the Bank of England looks to increase their base rate from 0.1% to 0.25%, with more possible hikes to follow. Labour, energy costs and supply chain issues are still causing problems for producers. Maybe this has something more to do with the billions the UK government has thrown into the economy in the past 18 months, rather than an unreliable link between inflation and unemployment.

Recent Blog Articles

Popular Products

This guide and its content is copyright of Chard (1964) Ltd - © Chard (1964) Ltd 2024. All rights reserved. Any redistribution or reproduction of part or all of the contents in any form is prohibited.

We are not financial advisers and we would always recommend that you consult with one prior to making any investment decision.

You can read more about copyright or our advice disclaimer on these links.