King William I (1066-1087)

Synopsis

A brief account of King William I, also known as William the Conqueror. King William I, also known as William the Conqueror, is primarily known as the victor at one of the most important events in English history, the Battle of Hastings, William, Duke of Normandy, would go on to found a whole new era in English history. One which would see the end of native English rule and the imposition of a new and foreign ruling class which would consider itself such for centuries afterwards.

William I Penny

Early Life

William was born to a tanner's daughter in 1028, the illegitimate son of Robert the Magnificent, Duke of Normandy. Robert did not acknowledge William as his heir until shortly before he died, leaving no legitimate heirs. In 1035, aged 7, William succeeded to the Dukedom of Normandy as William II.

He faced many threats to his life during his childhood from jealous kinsmen who felt that they had a more legitimate claim than the one they called 'William the Bastard'. Nevertheless, with the aid of his guardians and allies, notably Henry I of France, he managed to survive the attempts against his person and Dukedom, and went on to become one of the most powerful and feared nobles in France.

William the Warrior

From an early age, William was compelled to lead troops in battle to face down rebellions and later on, external threats, including from Henry I, his former ally, who launched two unsuccessful invasions in 1054 and 1057 with the aid of Geoffrey II of Anjou. Although he successfully defeated them, the Duke was wary of their powerful and aggressive nature. Their deaths in 1060 were a great benefit to the Duke and would allow him greater freedom of action elsewhere in the future.

Marriage

In 1053, William married his cousin, Matilda of Flanders. She had initially been reluctant to marry him due to his half-common and illegitimate status, but changed her mind when William burst into her home and beat her up until she finally accepted her marriage proposal. Due to the consanguineous nature of the marriage, William donated a church building near Caen in order to appease God and the clerical hierarchy.

Claim to the English Throne

William's dubious claim to the English throne existed through his great aunt Emma of Normandy, who had been married to Aethelred the Unready and Cnut of Denmark. The monkish Edward the Confessor was childless, and the succession to the English throne was in doubt. Harold Godwinsson, Earl of Wessex, was in the best position to succeed. In 1064 however, he was shipwrecked off the coast of Normandy. Whilst a guest at the Norman court, William allegedly fooled Harold into swearing to support William's own claim to the English throne. Whatever the truth of this allegation, Harold took no notice, and when the Confessor died in January of 1066, he had himself crowned as Harold II.

_from_NPG.jpg?1537884092817)

Portrait of King William I

William Invades England

Upon hearing of the Confessor's death and Harold II's coronation, William made preparations to invade England with an army consisting of Normans and mercenaries, bribed with promises of English land and titles. William also managed to obtain the Pope's blessing for the invasion, so that his army could fight under a papal banner. William was prevented from invading England straight away however, by the choppy waters of the English Channel. It would be 8 months before the channel was calm enough for the invasion fleet to cross, which it finally did in September.

Harold had been forced in the meantime, to march north and defeat a Danish Army led by Harald Hadrada of Norway and Harold's disaffected brother Tostig. Harold subsequently led his victorious but exhausted army back down south to confront William. William used this time to forage and plunder the surrounding area for supplies and prepare his army for the coming confrontation. Harold's army arrived near London 5 days later, and on October 12, he departed London and marched towards Hastings, gathering what reinforcements he could for his battered and tired army. He arrived near the following evening and took up a defensive position on Senlac Ridge to await the arrival of William the Bastard.

The Battle of Hastings, 1066

William's army arrived at dawn the following day. William decided to attack immediately before Anglo-Saxon reinforcements made Harold's army any stronger. If William failed to win here, his army would be destroyed, as would be his dream of becoming King of England. However, the Anglo-Saxon Shield walls proved to be robust enough to withstand the attacks, and each Norman assault was repelled with heavy losses. The fighting lasted all day, alternating between Norman archers attempting to soften up the Anglo-Saxon lines with arrows before cavalry and infantry attacked in order to try and break the shield wall. At one point, part of the Norman army broke and ran, pursued by Anglo-Saxons. A rumour arose that William had been killed, forcing William to lift his helmet and bellow out the falseness of the rumour. Thus he rallied his men and they turned around and slaughtered the pursuing Anglo Saxons, who were no longer protected by the shield wall.

With the shield wall now thinned out, the fyrdmen (poorly armed farmers drafted as militiamen) where easy targets for Norman archers and further assaults. At around this point, King Harold was killed, and the remainder of the English army broke and ran, except for the Housecarls (well-equipped professional warriors), many of whom stood and fought as a matter of pride and honour until they were inevitably struck down and killed by the triumphant Normans.

The cream of the Anglo-Saxon army, Harold Godwinsson, his brothers and much of the Anglo-Saxon Nobility were killed during the battle and its aftermath. William believed that his victory was so decisive that the surrender of the Anglo-Saxons and their acceptance of his rule was a foregone conclusion.

William the Conqueror

William's victory was not yet complete however. He rested his army near Hastings for a fortnight whilst he anticipated the arrival of the Anglo-Saxon earls giving their submission to his rule. This was not forthcoming however, as many of the Earls, notwithstanding the devastation of the noble and warrior classes at Hastings did not accept defeat so easily, and in London, the young Edgar the Aetheling, grandson of Edmund II Ironside, was proclaimed King by the Witenagemot (Anglo-Saxon council of nobles). William therefore marched on London. After initial resistance, London surrendered to William and Edgar was forced to abdicate in William's favour. William was crowned on Christmas day 1066, which was marred by a partial massacre of the Saxon nobles in attendance when their shouts of acclamation where mistaken by the Norman Guards for an uprising.

William's victory was not yet complete however. He rested his army near Hastings for a fortnight whilst he anticipated the arrival of the Anglo-Saxon earls giving their submission to his rule. This was not forthcoming however, as many of the Earls, notwithstanding the devastation of the noble and warrior classes at Hastings did not accept defeat so easily, and in London, the young Edgar the Aetheling, grandson of Edmund II Ironside, was proclaimed King by the Witenagemot (Anglo-Saxon council of nobles). William therefore marched on London. After initial resistance, London surrendered to William and Edgar was forced to abdicate in William's favour. William was crowned on Christmas day 1066, which was marred by a partial massacre of the Saxon nobles in attendance when their shouts of acclamation where mistaken by the Norman Guards for an uprising.

The Harrying of the North

Although the South of England had submitted to the Conqueror's rule, the North was unwilling to accept Norman rule, in 1068, a revolt in favour of Edgar the Aetheling broke out. The rebellion was crushed by William, and he enacted savage measures to ensure that the North would remain pacified. In the years leading up to 1072, whole villages where raized to the ground, crops burned, livestock slaughtered (along with their owners) and agricultural tools were destroyed. Even farmland was ploughed with salt as a throwback to the fate of Carthage in Roman times. Many northerners were reduced to cannibalism as a result and an estimated 100,000 people died as a result of the harrying. Many of William's chroniclers, even Normans generally favourable to him, condemned this genocidal brutality as a stain on both his rule and on his very soul.

Later Reign

After 1072, William spent most of his remaining reign in Normandy, consolidating his lands in France. In 1079, he faced a rebellion by his own son, Robert Curthose, as the result of his failure to punish his other sons, William Rufus and Henry Beauclerc for playing a prank on Robert. William himself was unhorsed and nearly killed by Robert in battle, and would have been so had he not identified himself to his son. In 1085, as part of a drive to increase administrative efficiency and taxation, he commissioned a comprehensive survey of England, the results of which were compiled in what is now known as the Domesday Book, completed in 1086, which listed every taxable property in England and its annual revenue.

Death

The following year, William was mortally injured in the abdomen when his horse stumbled whilst capturing the French town of Mantes from his nominal overlord the King of France. As he lay dying of peritonitis, he is said to have wept constantly in fear of going to Hell, perhaps out of guilt for the atrocities he had perpetrated during his lifetime, particularly in the North of England. Perhaps in part due to his antipathy towards his rebellious son Robert, he declined to leave him the Kingdom of England, but left him only the Dukedom of Normandy, leaving the kingdom to his younger son, William Rufus, who became William II of England. His youngest son, Henry Beauclerc, would also become King of England later. It is notable that the Bastard's (or Conqueror's) funeral was a disgusting and undignified affair. Immediately after his death, his servants robbed his body of all its valuables and clothes, leaving him sprawled naked over the stone floor. As his body was borne to its burial place in Caen, his corpse swelled in the heat, making his body too large to fit inside the stone sarcophagus. As the attendents tried to cram it in, the body burst open, spraying the putrefied contents of his abdomen all over the church and its attendant mourners. The rest of the funeral was hurried through in order that everyone could flee outside into the fresh air. In later years, his body would suffer the further indignity of disinterment by marauding Huguenots and later, French Revolutionaries, who stole what remained of the contents of the Conqueror's tomb.

Legacy

The legacy of the Conqueror is one where for centuries afterwards, England was run by a ruling class which considered itself foreign to those it ruled. Until the 15th century, the primary language of England's monarchy was Norman French, and amongst the nobility, to be described as an Englishman was considered a patronising insult. Under the Normans, the governance of England became more centralised, and centred around the Royal Court. Subsequent English Monarch's holdings in France led to centuries of mutual enmity and warfare between England and France as France sought to force the English Kings to pay homage for their French possessions as the English Kings sought to expand their French holdings at the expense of the French Monarchy.

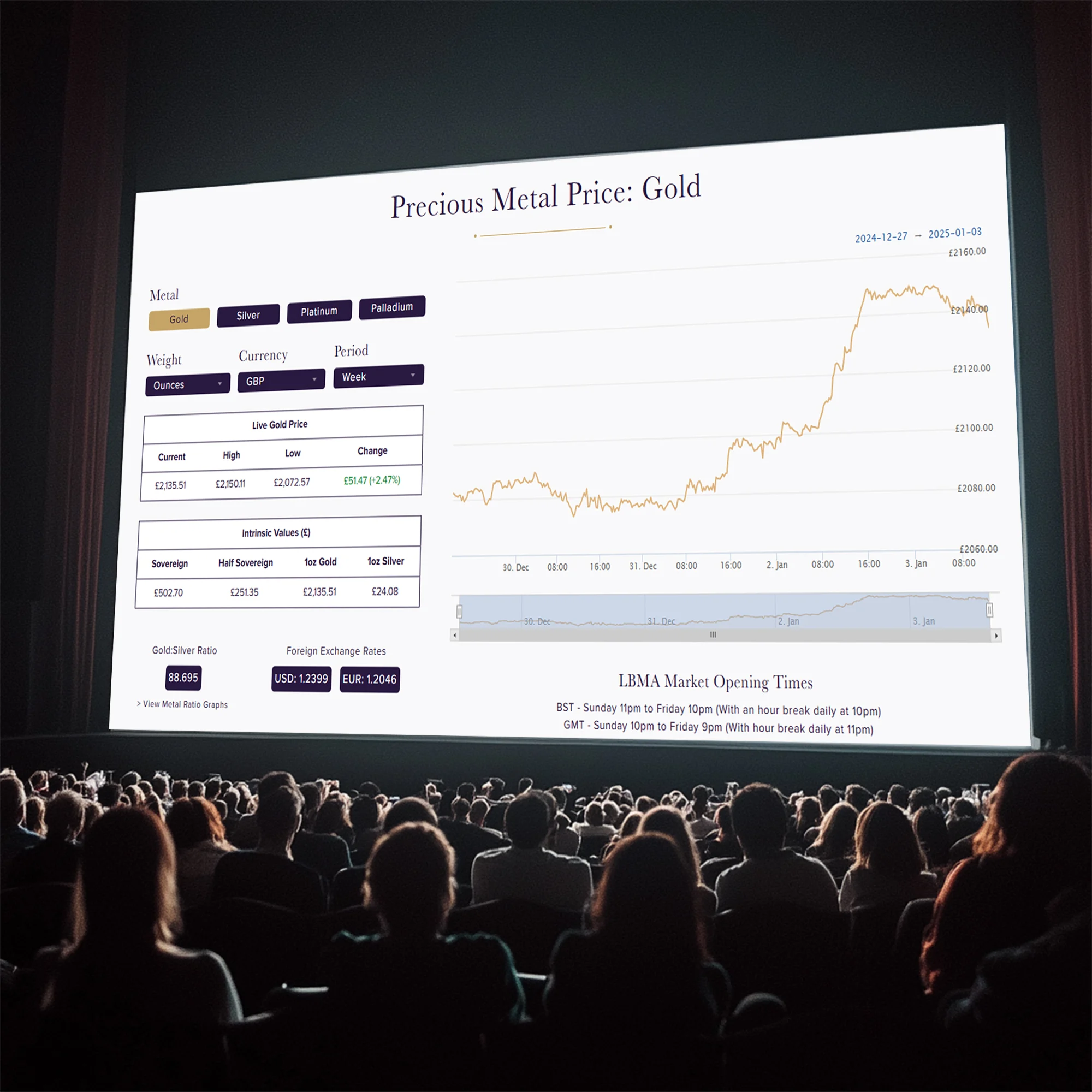

Numismatically, the style of the silver pennies issued in William's name where similar to those of his Anglo-Saxon predecessors. However, a monetary reform towards the end of his reign standardised the weight of the penny at 21.5 grains (approximately 1.4 grams) and fees imposed by the crown where reduced in return for a tax which depended on the revenue collected by the moneyer, which reduced the burden placed on the smaller moneyers whose turnover was less than those of the larger ones.

A history of Kings and Queens of England - Learn more about the Kings and Queens that reigned England throughout the different monarch dynasties (1066-2022).

Related Blog Articles

This guide and its content is copyright of Chard (1964) Ltd - © Chard (1964) Ltd 2025. All rights reserved. Any redistribution or reproduction of part or all of the contents in any form is prohibited.

We are not financial advisers and we would always recommend that you consult with one prior to making any investment decision.

You can read more about copyright or our advice disclaimer on these links.