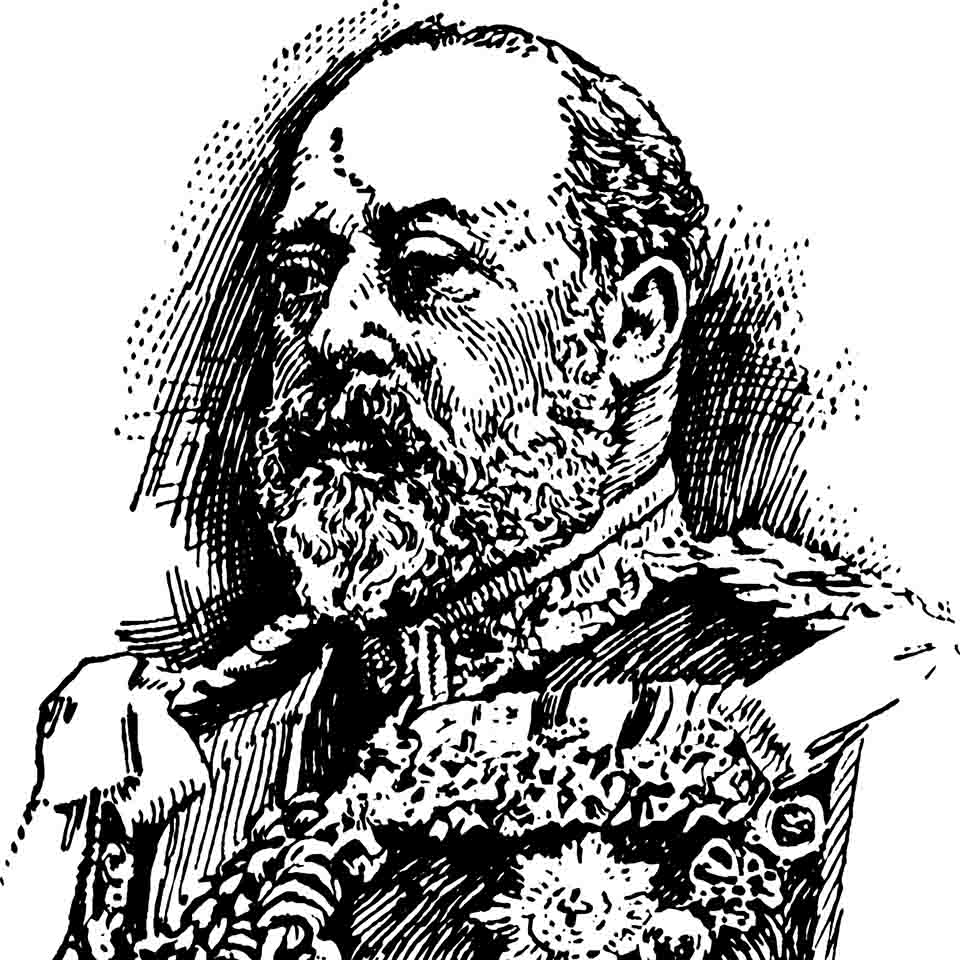

King George II (1727 - 1760)

Synopsis

George II was the second Hanoverian monarch to reign over Great Britain. He is primarily known for his poor relationship with his father and with his own son and heir, Frederick, Prince of Wales. His reign was also notable as a time of imperial expansion for Britain.

Early Life

George Augustus was born in Hanover on the 30th of October (OS) 1683, the only son of George Ludwig (later George I) and Sophia of Celle. George Augustus' parents divorced in 1694, and George's mother was imprisoned under house arrest for the rest of her life, and forbidden to have any further contact with her children. George, who was only 11 years old when his mother was forcibly removed from his life, would eventually come to hate his father, and the feeling became mutual.

In 1705, George Augustus married Caroline of Ansbach, with whom he was to have eight children. Also in that year, an Act of Succession was passed in Britain, placing George Augustus directly in line to the throne after his grandmother, Electress Sophia, and his father. This had been anticipated for some years, and George Augustus had learned to speak English fluently, in addition to French, Latin, Dutch and Spanish, as well as his native German. The 1705 act also made George a naturalised British subject, and he fought as a cavalry officer against the French under the Duke of Marlborough during the War of the Spanish Succession, taking part in the British and allied victory at the Battle of Oudenarde in 1708. Later on, he was to become the last British Monarch to personally lead his troops into Battle at the Battle of Dettingen in 1743.

The Hanoverian Succession

In 1714, Queen Anne died, and George's father came to the British throne as George I, whilst the younger George became Prince of Wales. George the Elder was not a very popular monarch with the British people or with many in the establishment. He could not speak English beyond a few simple words and phrases, and made plain his preference for his native Hanover by spending as much of his time there as he could, rather than in his new Kingdom. George, Prince of Wales, on the other hand, was a fluent English speaker (albeit heavily accented) and was much more popular than his dour father, and he delighted in exploiting this advantage, much to the jealousy of the George I. Matters came to a head in 1717, when a quarrel broke out over who should be godfather to George Augustus' son, Prince George William. The Prince of Wales exploded publically in his father's face at the suggestion that his estranged father should choose the godfather of HIS son, and the king subsequently had George arrested and then expelled from the court.

Following his exile from his father's court, the Prince set up his own rival court in Leicester House, to which his father's political opponents flocked. Although a reconciliation of sorts was arranged in 1720, father and son never truly got along. George I died whilst on one of his frequent visits to Hanover in 1727. It is said that when his son heard the news, he at first refused to believe it, suspecting that it was a trick designed to catch him out for expressing joy at his detested father's demise.

Reign

Nevertheless, the news of George I's death was indeed true, and George Augustus, Prince of Wales succeeded to the throne as George II. All those who had once been in the favour of his father could now expect to find themselves to be out of favour with the new Monarch. This might have been the fate of Sir Robert Walpole, the Prime Minister, who had in the eyes of George II, betrayed him whilst his father had been alive by abandoning his rival 'court' and gaining favour with his hated parent.

Nevertheless, Walpole enjoyed the favour of George II's beloved wife Caroline, and this soothed any irritation George might have felt for Walpole's previous adherence to the cause of the late king. Walpole continued to dominate British politics for over a decade, and Walpole, with the help of George II's relative indifference to politics, helped to cement the British transition from monarchical rule to parliamentary rule.

The family pattern of mutual antagonism between father and son continued however, when George II fell out with his eldest son, Frederick, Prince of Wales. Frederick had remained in Hanover as a child of 7 to fly the dynastic flag in the native land when his father and grandfather had moved to Britain following the Hanoverian succession in 1714. The future George II was to have little contact with his son until 1728, by which time Frederick had left childhood and was now a young man of 21. George II and his wife Caroline had by this point produced more children in Britain and established a new domestic household. They appeared to have forgotten their firstborn and viewed his newfound presence in Britain as that of an unwelcome stranger imposing himself upon them and their new family.

Predictably, Frederick did not take well to this treatment, and after being excluded from court, followed in his father's footsteps by setting up a rival court in his princely residence at Leicester House to give patronage to his father's opponents. Father and son remained at loggerheads for the rest of the latter's life. Frederick did not survive to succeed his father, and died in 1751, predeceasing his father by 9 years.

Rebellion and War

One group of people who delighted in the internal divisions within the House of Hanover were the Jacobites. In 1739, Britain and France went to war once again in the War of the Austrian Succession. Later, in 1745, a Jacobite army, led by the pretender Prince of Wales (Bonnie Prince Charlie) landed in Scotland in the name of his father, James, the old Pretender. This small force gathered support from many of the Highland clans and succeeded in driving the British Hanoverian Armies from Scotland, marching into England via Carlisle and Lancashire and was marching in the direction of London. Most of George II's troops in the early stages of the revolt were deployed in the continent, and England was essentially undefended. However, by the time the Jacobites reached Derby, some Government troops had been redeployed from the continent to deal with the Jacobite threat, and Bonnie Prince Charlie was forced to retreat. In 1746, at Culloden, Jacobite forces were forever destroyed by Redcoats led by Prince William, Duke of Cumberland, George II's younger son. At around the same time as the Jacobite rebellion, Admiral Anson returned from a successful naval expedition against the Spanish, during which he had captured a fortune in silver, which was subsequently conveyed to the tower and coined, with the word 'Lima' below the King's bust, as a taunt to the Spanish as to the origins of the silver used to strike the coins. The war did not all go Britain's way however, and eventually, a negotiated settlement was reached in 1748.

Later Reign and Death

When Frederick Prince of Wales died in 1751, his young son, George (later George III) became heir to the throne. George II took an interest in his young grandson, but his daughter in law, the Dowager Princess of Wales, refused allow her son to stay with the man who had estranged himself from her husband. The following year, an Act of Parliament decreed the adoption of the Gregorian calendar to replace the Julian one that had been in use since Roman times. Under this reform, the date went straight from the second of September (OS) into the 14th of September (NS), leading to riots from some quarters, from those who believed that they had been 'robbed' of 11 days of their lives.

In 1756, war once again broke out between France and Britain, in what became known as the Seven Years War, although the war went well for Britain, George did not live to see its conclusion. He died in 1760, leaving his grandson to ascend the throne as George III.

Legacy

George II's most important legacy is perhaps his lack of involvement in government, particularly in his later years. Although it would be wrong to say that the monarchy no longer had any power or influence, it had, under George II, given way to governance by a cabinet of ministers chosen largely by the Prime Minister, who gained his position not (by and large) due to the patronage of the monarch, but by the support he enjoyed in the House of Commons. Although a politicians career could still be helped or hindered by the attitude of the king, it could no longer be nakedly suppressed against the explicit will of Parliament.

George II's most important legacy is perhaps his lack of involvement in government, particularly in his later years. Although it would be wrong to say that the monarchy no longer had any power or influence, it had, under George II, given way to governance by a cabinet of ministers chosen largely by the Prime Minister, who gained his position not (by and large) due to the patronage of the monarch, but by the support he enjoyed in the House of Commons. Although a politicians career could still be helped or hindered by the attitude of the king, it could no longer be nakedly suppressed against the explicit will of Parliament.

The coinage of George II is notable for the 'Lima' issues as previously noted. One interesting fact about the 'Lima' issues of 1745-46 is that they are some of the most common silver coins of George II's reign. As the population increased in Britain due to the industrial revolution, a shortage of silver had already begun to take hold, causing a rise in the price of silver which often rose above the limit at which the Royal Mint was legally permitted to purchase for coin production. Consequently, the production of some coin types became sporadic, and the capture of Spanish silver bullion by Anson's squadron helped to alleviate a growing problem, at least temporarily.

However, the problem of rising metal prices and the subsequent shortages of coins would become much worse under the reign of his grandson, and the problem would not be fully resolved until many decades later, when George III himself was an old man in the final years of his own reign.

A history of Kings and Queens of England - Learn more about the Kings and Queens that reigned England throughout the different monarch dynasties (1066-2022).

Related Blog Articles

This guide and its content is copyright of Chard (1964) Ltd - © Chard (1964) Ltd 2025. All rights reserved. Any redistribution or reproduction of part or all of the contents in any form is prohibited.

We are not financial advisers and we would always recommend that you consult with one prior to making any investment decision.

You can read more about copyright or our advice disclaimer on these links.