Shakespeare – Coins and Money

Synopsis

We take at look at the 400th Anniversary of the Death of William Shakespeare and the way coins and money feature in his plays. Published - June 2016.

Money and coins are frequently mentioned in Shakespeare's plays. Both English and foreign coins were used during Elizabeth I and James I reigns.

Shakespeare – Coins and Money

We take at look at the 400th Anniversary of the Death of William Shakespeare and the way coins and money feature in his plays.

Shakespeare’s Plays; Coins and Money

The works of Shakespeare are peppered with quotations about coins, money, wealth and accounting. Similar to today, many people were concerned with wealth, and the lack of it, and the status and success, or troubles, that money can bring. Money was portrayed as both good and evil. Shakespeare made excellent use of money by referring to the coins and by the use of monetary metaphors in both his characters and situations.

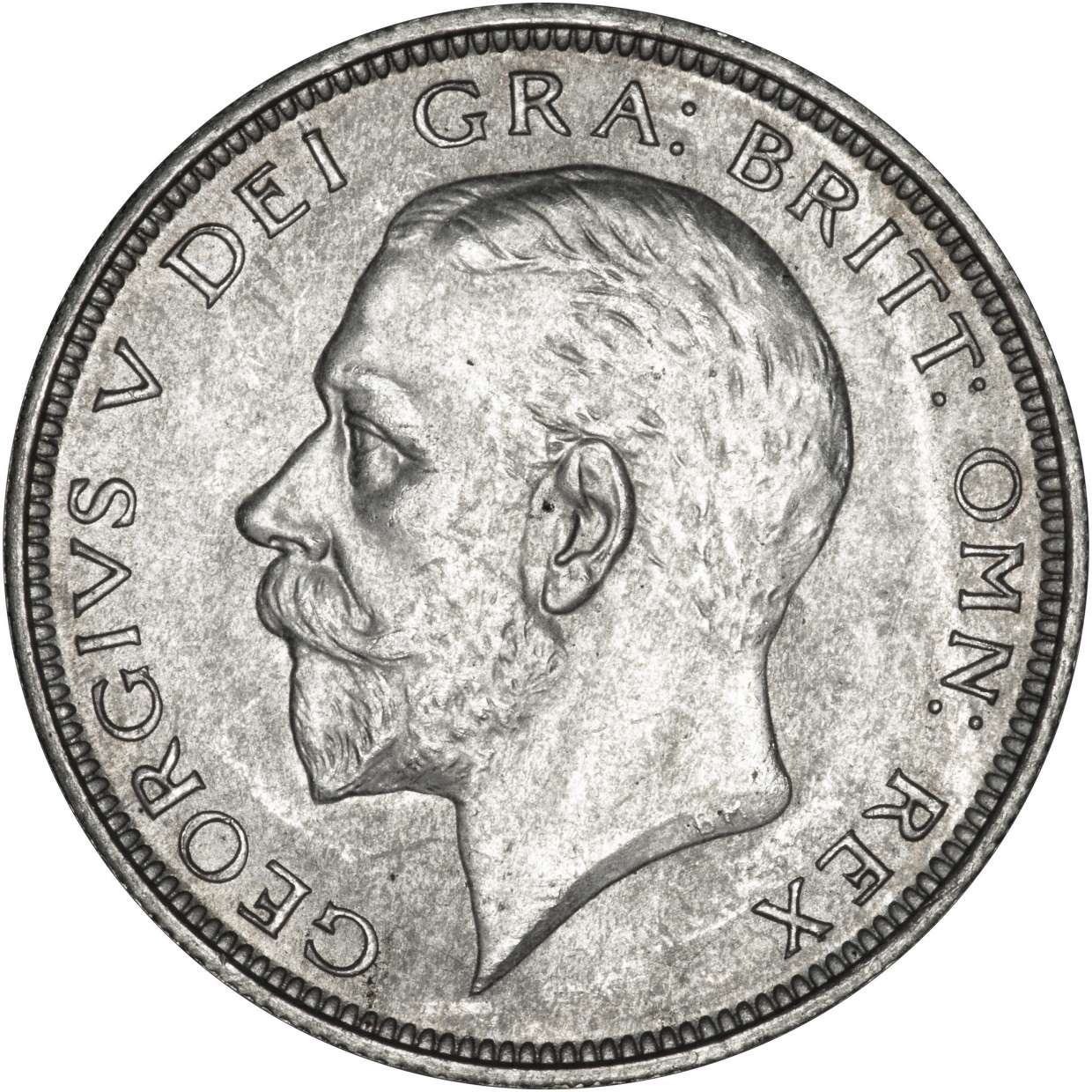

In Shakespeare’s time, coinage was measured in £.s.d. (pounds, shilling and pence or libra, solidus and denarius). With only gold or silver coins in use and 240 pennies to the pound, coins were an important part of everyday life. From the meanest silver halfpenny, penny and groat to the glorious gold sovereign, angel and ryal, the public were familiar with the many different types of coinage, including many foreign coins.

Shakespeare’s audience was becoming more cosmopolitan. Adventurers, such as Walter Raleigh and Francis Drake, had whetted the public’s appetite with their tales of exploration and great wealth that they presented to Queen Elizabeth I upon their return. Traders and travellers brought foreign coins back with them which corresponded to their intrinsic metal value and was accepted in lieu of payment. The ducat was a European coin, of both gold and silver which was accepted internationally.

The Merchant of Venice refers to the Venetian ducat (or duke’s coin). Subsequently, the ducat was adopted by a number of countries including Hungary, Austria, Denmark and the Netherlands. One rather wonders which upsets Shylock more, the loss of his money and jewels or that of his daughter, Jessica running off with a Christian?

Introduced in 1487, the tester, also known as a testoon, was the forerunner to the shilling and was worth twelve pence. The shilling is frequently mistakenly referred to in the symbol £.s.d. however, the ‘s.’ is actually based upon the Roman ‘solidus’ which was a denomination of a Roman coin. In The Two Gentlemen of Verona, the testern tip given by Proteus was poorly received by Speed, who thought this was paltry payment for his services.

Shakespeare and the Monarchs

Shakespeare wrote his plays and sonnets over the reigns of two monarchs; Elizabeth I and James I. He enjoyed patronage from both monarchs and gained both fame and wealth as an actor, playwright and theatre owner during their period of rule.

Elizabethan Coinage

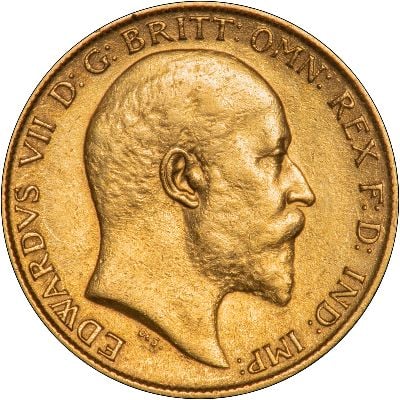

England prospered under the formidable Queen Elizabeth I, and her subjects, on the whole, adored her. She supported Literature and the Arts; playwrights, poets and artists flourished with her benefaction. Scientific innovation, political might and the expansion of international trade and exploration helped to ensure that England became stronger, wealthier and gained more prestige and power during the golden age of the Elizabethan Era. The number of coins imprinted with the portrait of Elizabeth I were prolific. It was a great exercise in propaganda to reinforce the public’s perception of the Queen. Everyone from the aristocracy to the poorest subject would carry coins featuring the Queen’s portrait upon their person.

Shakespeare made use of slang which his audience would recognise. The humble penny was often referred to as a cross due to the simple design on the reverse of the silver hammered coins of the time. The sixpence was one of the most popular Elizabethan coins. They were often referred to as counters and were sometimes used as a simple form of accounting, an easy type of abacus for the illiterate.

The reign of Elizabeth I is noted for the replacement of the debased coins of Henry VIII and restoration of silver coinage to the sterling standard of silver fineness 0.925. The term ‘Sterling’ was used in coinage to represent the standard fineness and also to exemplify commendable characteristics such as excellence, honesty, integrity and respectability.

Shakespeare uses sterling to identify with the king’s outstanding character in Richard II (A4,S1) “An if my word be sterling” and in a currency context in Henry IV Part 2 (A2,S1) “Pay her the debt you owe her, unpay the villainy you have done with her; the one you may do with sterling mony”.

In an age where a coin was supposed to be worth the intrinsic metal value, this helped to combat inflation and stabilise the economy. Coins were simply produced by hammering a piece of gold or silver between two coin dies. This led to coinage which was vulnerable to forgery and to being underweight. In 1562 there was a much needed progression from hammered coins to the brief introduction of the first milled coinage. Milled coins were harder to clip, shave and were more difficult to forge, unfortunately, they were also more expensive and slower to produce. This new process was vehemently opposed by mint workers and was shelved until the coinage of Charles II in 1662.

Whilst Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure concentrates on justice, integrity and clemency, it also lends itself to the serious matter of counterfeit currency and numerous metaphors can be found relating to coins and forgery. A fake coin was also known as a ‘slip’. It was a capital offence to be caught making or distributing counterfeit currency.

'Their saucy sweetness that do coin heaven’s image

In stamps that are forbid: ’tis all as easy

Falsely to take away a life true made

As to put metal in restrained means

To make a false one.'

Measure for Measure, Act 2, Scene 4'I am sorry, one so learned and so wise

As you, Lord Angelo, have still appear’d,

Should slip so grossly, both in the heat of blood.'

Measure for Measure, Act 5, Scene 1

Shakespeare plays upon Angelo’s name with the gold angel; of course, Angelo was no angel. Like many conmen, the self-serving Angelo, offers his ‘honourable’ character up for examination with the use of the play on words; mettle can be replaced with metal, noble can be translated from the virtuous trait to the gold Noble coin and, in this instance, ‘stamp’d’ relates to the image of arch-angel who is stamped upon the coin slaying a dragon.

'They have in England

a coin that bears the figure of an angel

Stamped in gold, but that’s insculped upon.

But here an angel in a golden bed'

Merchant of Venice, Act 2, Scene 7'And, ere our coming, see thou shake the bags

Of hoarding abbots; imprisoned angels'

The Life and Death of King John, Act 3, Scene 3

Jacobean Coinage

James I, King of Scotland, acceded the title of King of England upon the death of Elizabeth I in 1603, thus uniting the two realms and becoming the first King of Great Britain. Probably, the most noted coin of James I reign was the gold Unite coin; a symbolic result of the unification of England and Scotland. It had a face value of twenty shillings and was known as the Unit in Scotland.

James I had been well educated and was passionate about the theatre. Shakepeare made the wise move of renaming his acting company, The King’s Men in 1603 when James acceded the throne and wrote one of his most his most famous plays, Macbeth, during the Jacobean Era. This highly educated monarch with allegedly dubious morals is famous for authorising the King James I Bible and for quashing the Guy Fawkes Gunpowder Plot. His reign was filled with some beautiful gold coins which included the rose-ryal, the spur-ryal, the laurel.

Related Blog Articles

This guide and its content is copyright of Chard (1964) Ltd - © Chard (1964) Ltd 2024. All rights reserved. Any redistribution or reproduction of part or all of the contents in any form is prohibited.

We are not financial advisers and we would always recommend that you consult with one prior to making any investment decision.

You can read more about copyright or our advice disclaimer on these links.