Irish Coins

Synopsis

A brief history of Ireland & Irish coinage.

A Brief History of Ireland

The Republic of Ireland is a European country that covers the majority of the island of Ireland and was once part of a constituent country of the United Kingdom. Its capital is Dublin.

Early Irish History

Ireland was known to the Romans as Hibernia, and was populated by people belonging mostly to the Goidelic Celtic language group (as opposed to the Brythonic language group of mainland British Celts). There is evidence that trade existed between Ireland and the Roman Empire, but the Romans never made serious attempts to extend their power and influence over the Irish. At some point in the 5th Century, the Romano-British, Cumbrian-born St Patrick arrived on Ireland's shores to convert the local population to Christianity.

Ireland during the Middle Ages

From the 8th Century until the 11th, Ireland was almost as much of a victim of Viking predation as England during the same period, although Viking occupation was never as extensive as that of the Dane law in England, the Vikings did found Dublin as a Viking settlement, as well as a few other towns and cities, mainly along the coast.

Adrian IV, formerly known as Nicholas Breakspear and England's first and only Pope, issued a papal bull in 1155 urging the King of England to invade Ireland in order to bring the Celtic Church there under Roman Catholic authority. However, this instruction was not taken up immediately by the King.

In 1168 Diarmait Mac Murchada, the deposed King of Leinster appealed to Henry II of England for support in regaining his throne. Whilst in England, He met Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke (aka 'Strongbow'), who agreed to aid his efforts to regain the throne of Leinster and become the High King of Ireland. Strongbow, leading a force of Welsh Archers and Anglo-Norman cavalry and men-at-arms, proved to be very successful in their campaigns in Ireland, so successful infact, that Henry II of England feared that Strongbow's Irish holdings would make him an over mighty subject and a threat to his own authority in England. And so Strongbow was recalled to England and in 1171, Henry II landed in Ireland with his own invasion force, demanding and receiving recognition as Lord of Ireland from the local chieftains. Apart from a brief period when Prince John received the Lordship of Ireland before he became King, Ireland remained a Lordship under the English kings until 1536, when Henry VIII made it a separate kingdom, of which he and his successors were its monarchs.

Kingdom of Ireland

Along with the declaration Ireland becoming a kingdom, Henry VIII and his Tudor successors fought a series of campaigns to stamp their Royal authority over Ireland. However, it wasn't until the end of the 17th Century that English domination over Ireland was truly imposed. Most of the Irish, being Catholic, had the misfortune to be in the camp of the losing Royalist side of the 'English' Civil War against the largely Puritan Protestant Parliamentarians. A brutal struggle between Irish Royalists and their Allies against Cromwell's New Model Army resulted in a victory for Cromwell and led to a change in Ireland's ruling class and social structure, with Protestants becoming for the first time owning the majority of the land and effectively becoming its ruling elite.

1801 Act of Union

Despite English Domination over Ireland, it was effectively self-governing (or at least its native protestant elite governed it). However, the Napoleonic Wars and the unsuccessful 1798 Irish Rebellion led by Wolfe Tone, a protestant raised fears in Britain that Ireland could be a liability as a potential base for foreign invaders unless it could be fully integrated as part of the United Kingdom. And so in 1800, after negotiations (not to mention a heavy degree of bribery) Acts of Union were passed in both Parliaments that abolished the Irish Parliament and transferred representation to Westminster instead, coming into effect the following year.

Catholic Emancipation

The Act of Union had been passed with the support of many Roman Catholics in Ireland because the British Government, led by William Pitt the Younger, promised to introduce Catholic Emancipation to enfranchise Roman Catholics, who had been denied representation in both the British and Irish Parliaments. However, the pro-emancipationists hit a stumbling block when George III refused to sign any bill authorising emancipation, on the grounds that it would violate his coronation oath to maintain the privileges of the protestant church. Realising he was unable to maintain his promise to the Irish Catholics, Pitt resigned as Prime Minister.

The issue would continue to fester into the 1820s, when the Irish Barrister Danniel O'Connell engineered a constitutional crisis in 1828 by standing for and winning the Parliamentary seat for Clare, but was prevented from taking because of his Roman Catholicism. A bill emancipating Catholics was passed the following year, after George IV was persuaded by the Duke of Wellington and others to support its passage.

The Famine

In 1845, a Europe-wide potato blight and a bad harvest hit Ireland particularly hard. Ireland, being unusually bereft of natural resources, such as coal and iron was nowhere near as industrialised as other members of the United Kingdom and its economy was still primarily rural. Its population density was however, comparable to that of England at the time and the potato was extremely important as a sustenance crop grown by Irish labourers. The devastation wreaked by the blight led to starvation on a massive scale, especially as the famine lasted for over 7 years. Although famine relief and charity was generous at first, the length of the crisis caused 'compassion fatigue' and typically Victorian attitudes towards poverty began to harden as the Irish came to be perceived as indolent and lazy and thus at least in part the authors of their own misfortune. The often inadequate response of the British Government towards famine relief led to a perception amongst many Irish Nationalists and the Irish Dispora that the British response to the famine had been a deliberate act of genocide to reduce the population of Ireland to a more 'manageable' level. Whatever the truth of this, the population of Ireland crashed as a direct result of the famine. Ireland's population of over 8 million before the famine was drastically reduced during the famine and over the succeeding years, and with a population of just over 6 million today (including in Northern Ireland) the Irish population has still not fully recovered from this disaster.

The Irish Home Rule Movement

Irish Nationalism had existed long before the Famine, but in the years following this, the movement began to grow in earnest. At first, the majority of the Irish Nationalist Movement, as represented by the Irish Nationalist Party, had moderate demands, namely for Irish Home Rule within the British Empire. Led by Charles Stuart Parnell, the Irish Nationalist Party achieved some success by becoming a significant party within the House of Commons, supporting William Gladstone's Liberal Administrations in return for Gladstone's support for Home Rule. Gladstone was known to be sympathetic to moderate Irish Nationalist aspirations, and had, when first becoming Prime Minister in 1868, announced that it was his intention to 'Pacify* Ireland'. The Phoenix Park Murders of Chief Secretary of Ireland Lord Cavendish and Undersecretary Thomas Burke proved by Fenian extremists proved to be something of a setback for the moderate nationalist cause. An 1886 Home Rule Bill failed to pass a vote in the Commons. Gladstone subsequently resigned, having been in office for only a few months.

A Second Home Rule Bill in 1893 did pass a vote in the Commons. It was rejected by the Lords however, and failed to pass into law. A Third Home Rule Bill was introduced in 1912; it was again opposed by the Lords. This time however, thanks to the Parliament Act of 1911, The Lords could now only delay, and not stop legislation passed by the Commons. Thus, the Home Rule act of 1914 was passed into law. However, the start of World War I in that year caused the legislation to be shelved for the duration of hostilities.

*Although the use of the word 'pacify’ would imply brutal methods to modern ears, this was not how it would necessarily have been the case in 1868.

The Easter Rising

Ireland was divided over the issue of Home Rule. Most Irish Protestants, particularly those of Ulster, feared that Irish self-government would lead Catholic tyranny if Home Rule (which they called 'Rome Rule') was granted. When it became clear that Home Rule was inevitable, Protestant Unionists formed a Unionist Militia, known as the Ulster Volunteer Force, importing large quantities of guns and training them to resist the implementation of Home Rule. Irish Nationalists responded to this by forming the Irish Volunteers in order to fight any attempt to deny the Implementation of Home Rule.

The Outbreak of World War One led to a split in the Irish Volunteer movement. Whilst the Ulster Volunteer force was, not surprisingly, supportive of the British war effort, the Irish Volunteers were split between those who supported the British War effort (led by IPP leader John Redmond) and those who regarded WWI as a British War in which Irishmen should have no part (unless it was on the other side).

The UVF practically joined the War en masse, forming the core of the 36th (Ulster) Division of the British Army. The Irish Volunteers who supported the British War Effort became known as the National Volunteers, and fought in the British Army in the hopes of winning the war as quickly as possible in order that Home Rule would be delayed no longer than necessary.

However, Irish Republicanism, the militant side of Irish Nationalism, represented in large part by the Irish Republican Brotherhood, planned a general uprising for Easter 1916. With over a thousand volunteers, the Irish rebels took over several key strongpoints in Dublin, most notably the General Post Office, and hoped to inspire a general uprising amongst the Irish population. This turned into fiasco however, as the Irish population, many of whom had relatives serving in the British Army, was not sympathetic to the uprising. When the captured rebels were marched away by British soldiers, they endured boos from the assembled Dublin crowds. However, the attitude of the Irish population turned drastically when the British authorities made the political mistake of executing most of the captured ringleaders by firing squad.

Two and a half years later, the IPP was virtually wiped out by the Sinn Fein Party in the 1918 General Election. Sinn Fein's manifesto went beyond Home Rule in favour of complete independence. The victorious Sinn Fein candidates refused to take their seats in Westminster, and instead formed their own Irish Assembly or Dail. In January 1919, this Dail made a unilateral declaration of Independence in the name of the Irish Republic.

Irish War of Independence

Following the declaration of the Irish Republic, Armed bands of self-proclaimed IRA (Irish Republican Army) soldiers, sometimes acting alone, began to attack institutions and people they associated with British rule. Members of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), Soldiers, Protestant Landowners and Unionists where felled by bullets and bombs. In response, British soldiers, the RIC and Police Auxiliaries (consisting largely of de-mobbed soldiers whose skills were, not surprisingly, more geared towards warfare than policing, and often known as the 'black and tans') launched often brutal reprisals against Irish Republicans, armed or unarmed, perceived or real.

After two years of guerrilla warfare, most people both sides realised that they would have to compromise in order to end the war. The British knew that crushing the uprising would have cost too much in blood, treasure, public support and international good will than it was worth. The Irish Republican side for their part were running out of supplies and losing many people to the violence. It had also become apparent that their support in the North was very limited, and that the Unionist cause in Ulster was too strong for them to overcome. And so in 1922, the Anglo-Irish Treaty creating the Irish Free State in the South was signed, ending the Anglo-Irish War.

Irish Civil War

The Anglo-Irish treaty was not well received by a large section of the IRA however. It was seen as a betrayal of the Irish Republic that had been created in 1919. The Irish Free State excluded Ulster, and George V of Britain remained as the Free State's Head of State.

Fighting broke out between former comrades in the IRA, as the forces of the Free State, led by Michael Collins, fought against the anti-treaty IRA faction. Fighting between these two factions was at least as brutal, if not more so than that which had taken place between British and Irish combatants less than a year before. However, the pro-treaty side, with British material support, succeeded in triumphing over the anti-treaty side. Although not before Michael Collins was killed in an IRA ambush. (Very) broadly speaking, the pro-treaty side evolved into the Fine Gael political party, and the anti-treaty side faction led by Eamon de Valera emerged into the Fianna Fail Party.

Republic of Ireland

The Irish Free State eventually came to be led by Eamon de Valera in 1937, when he became Taoiseach (Prime Minister), and he adopted a policy of gradually de-anglicising Irish institutions. Although George VI remained nominally King of the Irish Free State until 1949, Ireland was almost a defacto republic already by that point, as de Valera had already created the office of President of Ireland in 1937.

Ireland remained neutral during World War II, although this period was known as 'the Emergency' because of the restrictions on imports and exports due to the German U-Boat Campaign, and the constant (and sometimes very real) threat of British re-occupation of Ireland to prevent it falling into the hands of Nazi Germany. The declaration of the Republic of Ireland in 1949 also removed Ireland from the Commonwealth, and Ireland has never reapplied for membership.

Throughout the 20th Century, especially from the 1960s until the late 1990s, the issue of Northern Ireland remained a serious and often violent political issue in Ireland, with fighting and acts of terrorism taking place in both Ireland and England over British rule in Northern Ireland. Northern Irish Republicans, holding on to bitter memories of the Irish Civil War, considered the Government of the Republic of Ireland an enemy almost as much as they did the British, often bitterly referring to the government in Dublin as that of the 'Free State' long after this had technically ceased to be the case. The Constitution of Republic of Ireland maintained its sovereignty over the whole island of Ireland until 1998, when under the Belfast Agreement which largely ended 'The Troubles' over Northern Ireland, this claim was removed as a concession to Northern Irish Unionists.

Ireland Today

Ireland became a member of the EEC in 1972 when both the UK and the Republic of Ireland were admitted as members. Ireland joined the Euro in 2002, however, in recent years; the economy of the Republic of Ireland has suffered, in part because of its membership of the common currency. The Fianna Fail led government was heavily defeated in the 2011 general election due to the financial crisis which has left the Republic facing huge debts.

Coinage of Ireland

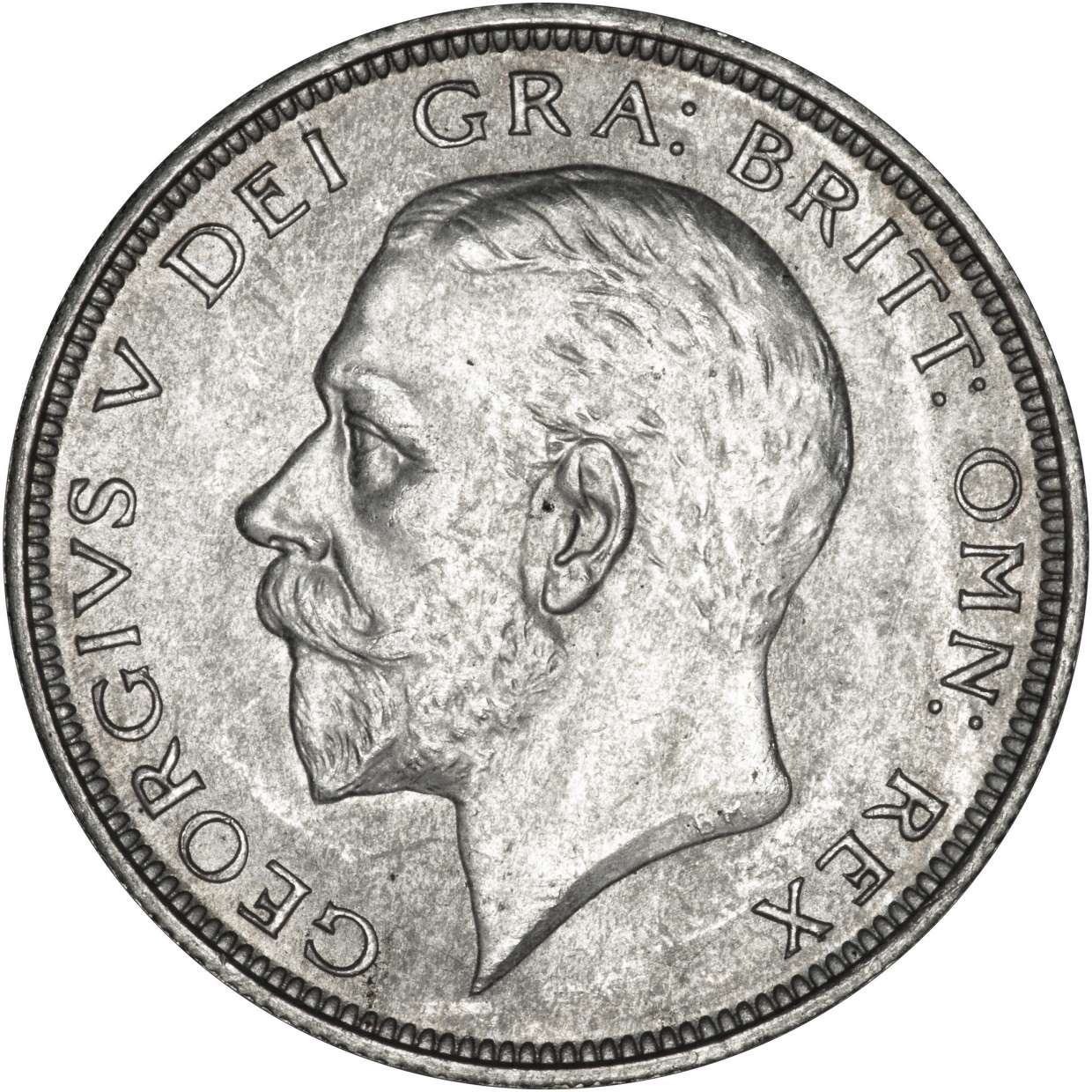

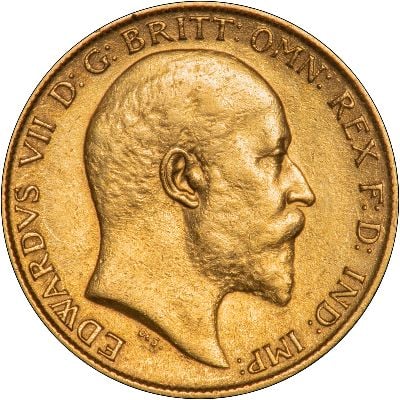

Roman coins have been discovered in Ireland, presumably as the result of trade between the locals and the Romans. However, the first coins issued in Ireland were Hiberno-Norse issues modelled after late Anglo-Saxon pennies. Following the Anglo-Norman invasions of the 12th Century, silver pennies modelled after the English issues were struck in Ireland (mainly Dublin) in the name of the Lords of Ireland.

From the Tudor Period onwards, Irish coins were typically debased compared to their English counterparts, in part for profit, but also to try and arrest the outflow of silver currency from Ireland that had become a problem there. Irish coins were often further differentiated from their English counterparts by the omission of a portrait on the obverse in favour of a harp or other symbol.

Despite this debasement, the Irish Pound diverged only slightly from the Pound Sterling. 13 pence Irish was worth 12 Pence Sterling, and this rate was fixed in 1701. Coins in the name of the Irish Pound were issued until 1826, when the Irish pound was abolished and replaced by the Pound Sterling.

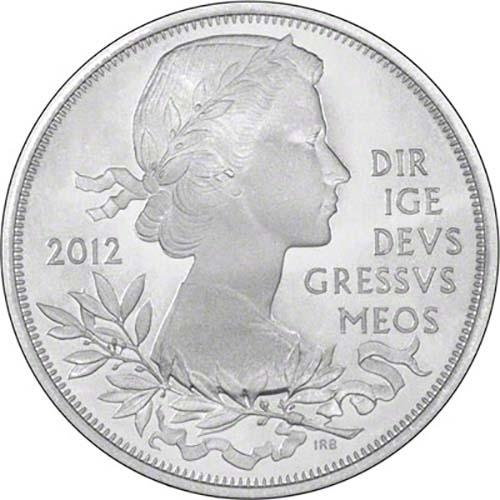

In 1926, a The Irish Free State passed a new Coinage Act to issue its own coins based on their British equivalents and pegged to the sterling at par. These coins typically featured animals on the reverse, along with the Irish Harp on the obverse. The Republic of Ireland decimalised alongside the UK in 1971, and introduced coins of the same size, value and weight as those of Britain. However, the par link between the Irish punt (pound) and the pound sterling was broken in 1979 when Ireland joined the exchange rate mechanism, which Britain stayed out of.

In 2002, Ireland entered the Euro, and the punt was abolished. Irish Euro coins generally feature the Irish Harp that has graced the obverse of most Irish coins since independence.

For Sale and Wanted

If you are interested in coins from Ireland please see our product index:- Irish Coins

Related Blog Articles

This guide and its content is copyright of Chard (1964) Ltd - © Chard (1964) Ltd 2025. All rights reserved. Any redistribution or reproduction of part or all of the contents in any form is prohibited.

We are not financial advisers and we would always recommend that you consult with one prior to making any investment decision.

You can read more about copyright or our advice disclaimer on these links.